Opening with a "true story" opening crawl - a conceited yet commercially successful ploy to attract a broader audience - Tobe Hooper's "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre", combined with symbolism as a banned video nasty, resonated with its target demographic, but not so with myopic critics, who failed to recognise the film's underlying social commentary, subtext and technical merits, wrongly deriding it as a threat to decency. Ironically, any onscreen violence therein occurs unexpectedly, most of it bloodless and relatively tame by horror standards; the film's unique ability to disturb and horrify arises purely from its relentless psychological impact, primarily in the use of percussive, screeching sound design, radical camera and lighting techniques, real time and agile, accomplished editing to build a foreboding sense of disquiet and accumulating apprehension. Rather than lulling his audience into a false sense of security, Hooper boldly shocks them outright with a lingering shot of a dead armadillo, Polaroid flashes illuminating desecrated corpses and audible news reports on said debased activity within the area reverberate throughout the credits. In compounding the simmering revulsion and disconcert beyond the film's initial focus on organically ghoulish, jarring imagery, the plot is seemingly unfurled at a largely unhurried pace, enabling the scorched, bleak scenery of Texas and its dilapidated buildings and homes to assume an offensive, downright lurid visual dominion over the tone and mood, eliminating the supernatural and replacing it with the dysfunctional Middle American family as a source of conceivable, unavoidable horror hiding in plain sight, from desiccated grandpas to feather-laden living rooms, the rural life of Texans has never been so disturbingly depicted and yet so startlingly candid. In capturing the foibles of a family affected by the hidden, backwoods element of the USA, Hooper changed the face of horror, ensuring that audiences could not feel assured of their safety; the ordeal endured by the characters herein was a distinct possibility since it was not some fantastical monster from outer space. In terms of originality, the level of violence is depicted subliminally, and therefore so indirectly diffusive and credible that you can hear the bones crunching under feet, smell the feverish hysteria, sweltering heat, rotting flesh, and body odour; dense with pervading aesthetic so fervent and visibly meretricious, the obviously inexpensive production values actually enhance and elevate the frenzied cumulative aura of madness and macabre. Hooper's adroit direction grounds the audience into a dark universe, thus set the template for twisted corporeal artistry, however, since its release in 1973, no other film within the genre has even come close to achieving its uniquely grubby, scabrous look or striking capacity to deeply unsettle and upset.

Sacrilege, impiety and irreverence pervade the atmosphere from the outset; a sudden commencement of splenetic, ominous truculence appears in the form of a hitchhiker picked up by a set of teenagers investigating the aforementioned reports of grave robbing. Upon ejecting the Polaroid-wielding hitchhiker when he turns grievously violent, the teenagers venture on to their old crumbling homestead, leaving in search of a swimming hole and a source of fuel, only to find a family of cannibal ex-slaughterhouse workers. Resplendent in its sun-burnt, permeable, quasi-documentary visual style, the film harnesses the hazy, surreal quality of a nightmare. Hooper's apocalyptic landscape is a dismal wasteland of decay and disuse, both in terms of workers and small businesses; the family who terrorise the aforementioned teenagers are depicted as victims of post-Vietnam industrial capitalism. In a more explicit sense than previous horror films exploring the American underbelly, a portentous, angst-laden ambience surrounds both families in the film; the nuclear unit as we know it is destroyed, replaced with post-Vietnam disillusionment and unemployment. Hooper's attack on contemporary American life is carried to a more logical conclusion than other films of its ilk, such as "Last House on the Left", in its addressing of the collapse of civil order, causality of violence and illegitimacy of authority as being the direct result of post-war malaise. Hooper subverts our preconceived idea of family values, exploring the textbook American Gothic family of the Saywers and presenting them as the hostile inversion of virtue and convention; the grubby, off-kilter kinship group herein represent the patriarchal regression of the nuclear family unit, rendered obsolete by large corporations and technology. In terms of dynamics and gender roles, the youngest son and the film's main source of physical horror, undertakes both male and female household duties, wearing alternating masks for each role composited from the skins of his victims. So efficacious is the character development and nuances in Leatherface's behaviour, interactions with other family members and environment, that upon reflection, he registers as deeply enigmatic, mythical and laconic, akin to Frankenstein's Monster.

Hooper's distinction herein is the assault on the senses that occurs throughout, as well as the intentional, extremely dark, ironic humour utilised to counter and punctuate the visceral aspects of the film, carefully measured so as not to diminish the film's overwhelming intensity. In the involving of the audience on a sensory level rather than intellectual, the film becomes deeply evocative, immersive and imbued with such sheer ugliness that it embodies horror, punishing the viewer in a raw, primal, nerve-shattering capacity. One cannot escape from it, nor does one want to escape; it is a contradictory state of mind that the viewer enters, both repelled and compelled by the chain of life depicted on screen, the jarring prospect of humans in the position of livestock effectively demystifies the brutal process of slaughtering and eating animals, especially when one character is impaled on a meat-hook and another is stunned by a sledgehammer. Every frame oozes with sweat-soaked hopelessness, creating a general feeling of disgust by the time the deranged slaughterer Leatherface chases his final victim with the titular chainsaw onto the dusk-lit road, a pursuit so protracted that it becomes almost unbearable to watch. However, from this seemingly prolonged unease comes sudden reprieve, as the final girl somehow outruns Leatherface and the ordeal concludes with his chainsaw buzzing and waving furiously as a sun set blazes within the frame.

"The Texas Chainsaw Massacre" is the grittiest and grimiest horror film you will ever see, an experience achingly close to spending the night in a slaughterhouse; encapsulating absurdity in a frighteningly realistic fashion, edifying a menagerie of characters whose way of life is at odds with our own but only slightly differing in our views of what constitutes meat, the film is executed with such spontaneity and verve that its low budget and lack of gore is what separates it from most horror films in that it genuinely horrifies.

All reviews -

Movies (55)

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre review

Posted : 5 years, 8 months ago on 11 October 2019 01:23

(A review of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre)

Posted : 5 years, 8 months ago on 11 October 2019 01:23

(A review of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) 0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Dawn of the Dead review

Posted : 5 years, 8 months ago on 10 October 2019 06:30

(A review of Dawn of the Dead)

Posted : 5 years, 8 months ago on 10 October 2019 06:30

(A review of Dawn of the Dead)"Dawn of the Dead" is not simply an extension of George A. Romero's debut "Night of the Living Dead", it is a complete overhaul, expanding on every aspect of the original whilst retaining a low-budget sensibility without diminishing the quality of the production. However, the main premise remains: social order has once again collapsed with the inexplicable reanimation of corpses. Rural communities are not overrun but the urban centres are swarming with zombie hordes all returning to the places instinctive to them. Crucially, this distinguishes "Dawn of the Dead" from its predecessor. "Night of the Living Dead" concentrated its action on an isolated rural house and limited the number of zombies, whereas "Dawn of the Dead" consolidates its activity within the confines of a shopping mall, thus inflating the possibilities of the story and its commentary on human nature in the event of disaster, i.e. those who capitalise on the opportunity to indulge in whatever civil and criminal law forbade them from doing (embodied as racist SWAT team officers, rednecks, militant biker gangs). Bolstered by a cast of actors who are able to act (in contrast to his first film) Romero's new band of gutsy, somewhat parsimonious, and therefore more identifiable, survivors are a pair of SWAT team members and a pregnant TV news broadcaster couple, i.e. characters able to rationalise and deal with a crisis without descending into hysteria and anarchy.

Once holed up in a shopping mall after eradicating the interior undead and blocking off the entrance, one of the SWAT team members becomes reckless and ends up bitten, leading the gang to fulfil their consumerist fantasies and end up corrupted by hedonism and materialism. In adding exposition and potency to the proceedings, Romero's follow-up to his lo-fi zombie allegory of the previous decade has still not been surpassed. Taking refuge in a shopping mall is exactly what rational survivors would do, but in doing so, the characters are infiltrated by the mindless consumerist values affecting the zombie plague who return instinctively to the place they know best. It is testament to Romero's vision that the indoor mall, even replete with the walking dead, actually resembles the reality of shopping centres in any part of the developing world. In being provided with endless convenience and epicurean enjoyment until the world ends, the film's characters are rendered as brainless as the corpses they view as inferior. Operating on the surface as an indictment of capitalism at large, and how it effectively turns us all into zombies, the pessimistic allegorical elements of "Dawn of the Dead" elevate the film into the annals of cinema history, beyond the usual intelligent, more sophisticated horror classics afforded such reverence; Romero's prescient sophomore zombie outing has lost none of its ability to shock, and is perhaps as damning and scathing of modern society (alive or dead) than any other film of its ilk. By developing the script's themes with explicit satirical subtext applied to the living under siege context, interesting (but still wooden) characters and uniformly more proficient (and gory) special effects, Romero's game-changing revision of his weak debut is broader, infinitely more compelling and in turn, the far superior work of prophetic, deliriously grisly satire.

Once holed up in a shopping mall after eradicating the interior undead and blocking off the entrance, one of the SWAT team members becomes reckless and ends up bitten, leading the gang to fulfil their consumerist fantasies and end up corrupted by hedonism and materialism. In adding exposition and potency to the proceedings, Romero's follow-up to his lo-fi zombie allegory of the previous decade has still not been surpassed. Taking refuge in a shopping mall is exactly what rational survivors would do, but in doing so, the characters are infiltrated by the mindless consumerist values affecting the zombie plague who return instinctively to the place they know best. It is testament to Romero's vision that the indoor mall, even replete with the walking dead, actually resembles the reality of shopping centres in any part of the developing world. In being provided with endless convenience and epicurean enjoyment until the world ends, the film's characters are rendered as brainless as the corpses they view as inferior. Operating on the surface as an indictment of capitalism at large, and how it effectively turns us all into zombies, the pessimistic allegorical elements of "Dawn of the Dead" elevate the film into the annals of cinema history, beyond the usual intelligent, more sophisticated horror classics afforded such reverence; Romero's prescient sophomore zombie outing has lost none of its ability to shock, and is perhaps as damning and scathing of modern society (alive or dead) than any other film of its ilk. By developing the script's themes with explicit satirical subtext applied to the living under siege context, interesting (but still wooden) characters and uniformly more proficient (and gory) special effects, Romero's game-changing revision of his weak debut is broader, infinitely more compelling and in turn, the far superior work of prophetic, deliriously grisly satire.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Wizard of Oz review

Posted : 5 years, 8 months ago on 9 October 2019 07:56

(A review of The Wizard of Oz)

Posted : 5 years, 8 months ago on 9 October 2019 07:56

(A review of The Wizard of Oz)Dorthy Gale is transported to the Land of Oz as the door from drab, sepia-toned, tornado ravaged Kansas opens up into brilliant, vibrant Technicolor; journeying to the fabled Emerald City via the infamous Yellow Brick Road, a quest begins, but only for the express purpose of returning home. Oz is ostensibly a magical, mysterious plane existing within Dorothy's dream state (rendered upon being knocked unconscious whilst fleeing her aunt's farm to prevent a particularly vile neighbour from euthanizing her dog Toto) inhabited by a quintet of dual characters physically transformed from their real-life counterparts. However, our heroine's vivid imagination prevails, thus conjuring a cavalcade of Munchkins governed by a supposedly all-powerful Wizard and besieged by two Wicked Witches, one of whom ends up squashed to death under the Kansas house and loses her magical ruby slippers to Dorothy, incurring the vengeful wrath of her sister, the Wicked Witch of the West. Such indelible characters serve to embellish and expand the intensely hued, irrepressible, optically magnificent world of Oz, artfully realised with monolithic matte paintings and dazzling special effects (the poppy field, cyclone, Emerald City views, flying monkeys) ensuring that the film is an immersive feat of the visual element from the outset.

Dorothy's drab existence as a lonely farm girl may pale in comparison to her exhilarating adventures in Oz, but her emphatic declaration of 'there's no place like home' highlights the allegorical connections and linkages to the 1896 political landscape within the film; the Scarecrow representing the wise, but naive western farmers, the Tinman - the dehumanised, Eastern factory workers, the Wicked Witch of the East - the Eastern industrialists and bankers who controlled the people (the Munchkins), the Good Witch of the North - New England, a stronghold of Populists, the Wizard - President Grover Cleveland, or Republican Presidential candidate William McKinley, the Cowardly Lion - Democratic-Populist Presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, Dorothy - the good natured American people, the Yellow Brick road - the 'gold standard' - paved with gold, but leads nowhere, the land of Oz - oz. is the standard abbreviation for ounce, in accordance with the other symbolism, Emerald City - Washington, D.C., with a greenish colour associated with greenbacks, the Poppy field - the threat of anti-imperialism. "The Wizard of Oz" is as electrifying to witness now as it must have been back in 1939, an age in which Hollywood championed idealism and escapism as integral to the cinematic experience rather than purely to garner profit and acclaim; filmmakers cared about the audience, offering them a much-needed uplifting respite from war, weariness and woe. Even though contemporary audiences are infinitely more familiar with CGI and bombastic sound effects than the relatively simple charms on display here, in an era of widespread political and economic upheaval, the film not only registers as both national relic, artefact and masterpiece of a Golden Age in cinema history, but an important rite of passage. Dorothy's timeless rendition of "Over the Rainbow" should reduce any child, regardless of the generation gap, to tears of joy at the perceived message that dreams can come true.

"The Wizard of Oz", despite the superannuated era-specific effects, performances and art design, caters to every demographic and remains effective in positing the optimistic, universal directive that, even in a world as bleak and cruel as ours, home is where the heart is. A true Hollywood treasure that still holds up well even 80 years on from its original release, however, scrutinise it for its faults and you are missing the point entirely; the film taps into our collective childlike sense of wonderment, elation and fervour, its images, dialogue, music and characters remain seared into the public consciousness. Beloved and fondly remembered, this deserved classic cannot be lauded enough, it is a superlative work of artistic and technical majesty that operates on the surface as an unmissable fantasy ride but is something far more emotionally resonant and life-affirming at its core.

Dorothy's drab existence as a lonely farm girl may pale in comparison to her exhilarating adventures in Oz, but her emphatic declaration of 'there's no place like home' highlights the allegorical connections and linkages to the 1896 political landscape within the film; the Scarecrow representing the wise, but naive western farmers, the Tinman - the dehumanised, Eastern factory workers, the Wicked Witch of the East - the Eastern industrialists and bankers who controlled the people (the Munchkins), the Good Witch of the North - New England, a stronghold of Populists, the Wizard - President Grover Cleveland, or Republican Presidential candidate William McKinley, the Cowardly Lion - Democratic-Populist Presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, Dorothy - the good natured American people, the Yellow Brick road - the 'gold standard' - paved with gold, but leads nowhere, the land of Oz - oz. is the standard abbreviation for ounce, in accordance with the other symbolism, Emerald City - Washington, D.C., with a greenish colour associated with greenbacks, the Poppy field - the threat of anti-imperialism. "The Wizard of Oz" is as electrifying to witness now as it must have been back in 1939, an age in which Hollywood championed idealism and escapism as integral to the cinematic experience rather than purely to garner profit and acclaim; filmmakers cared about the audience, offering them a much-needed uplifting respite from war, weariness and woe. Even though contemporary audiences are infinitely more familiar with CGI and bombastic sound effects than the relatively simple charms on display here, in an era of widespread political and economic upheaval, the film not only registers as both national relic, artefact and masterpiece of a Golden Age in cinema history, but an important rite of passage. Dorothy's timeless rendition of "Over the Rainbow" should reduce any child, regardless of the generation gap, to tears of joy at the perceived message that dreams can come true.

"The Wizard of Oz", despite the superannuated era-specific effects, performances and art design, caters to every demographic and remains effective in positing the optimistic, universal directive that, even in a world as bleak and cruel as ours, home is where the heart is. A true Hollywood treasure that still holds up well even 80 years on from its original release, however, scrutinise it for its faults and you are missing the point entirely; the film taps into our collective childlike sense of wonderment, elation and fervour, its images, dialogue, music and characters remain seared into the public consciousness. Beloved and fondly remembered, this deserved classic cannot be lauded enough, it is a superlative work of artistic and technical majesty that operates on the surface as an unmissable fantasy ride but is something far more emotionally resonant and life-affirming at its core.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Halloween review

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 8 October 2019 02:26

(A review of Halloween)

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 8 October 2019 02:26

(A review of Halloween)Conferred as a byword for the seasonal holiday it exploits as a thematic subtext and in-film catalyst, John Carpenter's "Halloween" is also fundamentally synonymous with popularising the slasher subgenre. Despite its basic concept, scope and budget, "Halloween" redefined the maxim and enacted conventions of the modern horror film paradigm, deriving a nascent dynamic whereby the figurehead of the story becomes inextricably linked with the heroine touted as a victim only to become his foe; the pursuit between the two and ensuing human collateral is relentless and inexplicable, instigating a mythology and generating a continuity franchise that appeals to new generations of horror fans.

As is typical for the genre, a remote, condensed narrative, an independent ethos and sparse production values is employed in order to resonate with and satisfying the mainstream audience on a primal level, channelling the suburbanite's subconscious fear of falling to prey to an incarnate, indestructible, implacable evil. Contrary to popular belief, the template of the slasher film formula manifested far earlier within the Grand Guignol and Giallo subgenres. "Halloween" deftly employs the violence and sexuality dichotomy; featuring first-person camera shots first showcased in prototypical slasher precursors "Black Christmas", "Eyes Without A Face", "Psycho" and "Peeping Tom", the execution of this technique distinguishes a disturbing sense of complicity and anticipation. Herein, the aforementioned evil is mute, therefore inscrutable, impenetrable and unstoppable, whereas in "Psycho" and "Peeping Tom", the focal character faces justice and is generally more sympathetic and rooted in reality.

"Halloween" exists within the suspenseful, dread-laden vacuum of Haddonfield, and its driving force is a simple but ingenious plot device: a killer who cannot be detected (because he only kills at Halloween, hiding in plain sight as a masked part of the proceedings). So remarkably effective was the foreboding presence of a motiveless killer terrorising a suburban town that it spawned a national boogeyman in Michael Myers/The Shape, a William Shatner mask (therefore heavy breathing - another tactic to provoke anxiety and build tension) and blue boiler suit-wearing personification of evil (he never dies) stabbed repeatedly by his final would-be victim, a frustrated, repressed girl who fears and therefore believes in him - not the sexually voracious and preoccupied type he previously dispatched - lending credence to the notion that the film is not an allegory or a moral statement, even though such themes are unarguably present, but an insight into the behaviour of a psychopath who stalks and kills on Halloween so as to revisit and relive the initial, defining characteristic in his methodology: the grisly murder of his older sister, who for him represents and embodies all aimless, nonchalant teenagers. Michael Myers blankly and silently surveys the area until the hour of his first murder is reached and therefore the conditions of his first murder are met; it is through this activity we observe the lives of his later victims. It is through this mundane, casual atmosphere, as with the opening scene demonstrating Michael's escape, that a haunting mood punctuated by The Shape's sudden appearances and disappearances and context are generated; the hunting behaviour of our antagonist develops into homicidal intent, juxtaposing the carefree mentality of the residents of Haddonfield and the sense of doom pervading every facet of the surroundings.

Carpenter's allusions to 1960s European and US horror cinema are present from the outset, and his foreground and background visuals are strikingly effectual, but such an exercise in atmospheric thrills with minimal character development, frequent audience identification with the villain and influencing a subgenre that descended into misogyny and gratuitous violence has drawn criticism rather than reverence, as is the case with Alfred Hitchcock's more explicitly violent post-1950 output ("Psycho" and "Frenzy"). However, the film is now considered an unmitigated classic of the genre and enjoys a reputation as such, even with modern audiences, but not so with a minority of seasoned, conservative and liberal critics. Perhaps many misinterpreted Carpenter's intentions - he understands the genre, and can therefore capitalise on it beyond the superficial - but reappraisal of his work has allowed for revision of said negative opinions; the film captures the energy of independent cinema in its singular vision, i.e. a haunted house movie extrapolated within a town, and in Carpenter's adept manipulation of the audience instead of focusing on the more derivative, psychosexual aspects, the use of psychological horror and scares build towards an onslaught of murders relatively restrained by today's standards. At its core, combined with appropriate musical cues from the keyboard score, the exuding dread and classic components of the genre, "Halloween" is a powerful, menacing indie movie that has become a staple of horror cinema, a cogently written, stylishly shot and visceral experience in slow-building terror. Existing purely through inspiration and purpose, it is entirely deserving of its acclaim and worthy of repeat viewings.

As is typical for the genre, a remote, condensed narrative, an independent ethos and sparse production values is employed in order to resonate with and satisfying the mainstream audience on a primal level, channelling the suburbanite's subconscious fear of falling to prey to an incarnate, indestructible, implacable evil. Contrary to popular belief, the template of the slasher film formula manifested far earlier within the Grand Guignol and Giallo subgenres. "Halloween" deftly employs the violence and sexuality dichotomy; featuring first-person camera shots first showcased in prototypical slasher precursors "Black Christmas", "Eyes Without A Face", "Psycho" and "Peeping Tom", the execution of this technique distinguishes a disturbing sense of complicity and anticipation. Herein, the aforementioned evil is mute, therefore inscrutable, impenetrable and unstoppable, whereas in "Psycho" and "Peeping Tom", the focal character faces justice and is generally more sympathetic and rooted in reality.

"Halloween" exists within the suspenseful, dread-laden vacuum of Haddonfield, and its driving force is a simple but ingenious plot device: a killer who cannot be detected (because he only kills at Halloween, hiding in plain sight as a masked part of the proceedings). So remarkably effective was the foreboding presence of a motiveless killer terrorising a suburban town that it spawned a national boogeyman in Michael Myers/The Shape, a William Shatner mask (therefore heavy breathing - another tactic to provoke anxiety and build tension) and blue boiler suit-wearing personification of evil (he never dies) stabbed repeatedly by his final would-be victim, a frustrated, repressed girl who fears and therefore believes in him - not the sexually voracious and preoccupied type he previously dispatched - lending credence to the notion that the film is not an allegory or a moral statement, even though such themes are unarguably present, but an insight into the behaviour of a psychopath who stalks and kills on Halloween so as to revisit and relive the initial, defining characteristic in his methodology: the grisly murder of his older sister, who for him represents and embodies all aimless, nonchalant teenagers. Michael Myers blankly and silently surveys the area until the hour of his first murder is reached and therefore the conditions of his first murder are met; it is through this activity we observe the lives of his later victims. It is through this mundane, casual atmosphere, as with the opening scene demonstrating Michael's escape, that a haunting mood punctuated by The Shape's sudden appearances and disappearances and context are generated; the hunting behaviour of our antagonist develops into homicidal intent, juxtaposing the carefree mentality of the residents of Haddonfield and the sense of doom pervading every facet of the surroundings.

Carpenter's allusions to 1960s European and US horror cinema are present from the outset, and his foreground and background visuals are strikingly effectual, but such an exercise in atmospheric thrills with minimal character development, frequent audience identification with the villain and influencing a subgenre that descended into misogyny and gratuitous violence has drawn criticism rather than reverence, as is the case with Alfred Hitchcock's more explicitly violent post-1950 output ("Psycho" and "Frenzy"). However, the film is now considered an unmitigated classic of the genre and enjoys a reputation as such, even with modern audiences, but not so with a minority of seasoned, conservative and liberal critics. Perhaps many misinterpreted Carpenter's intentions - he understands the genre, and can therefore capitalise on it beyond the superficial - but reappraisal of his work has allowed for revision of said negative opinions; the film captures the energy of independent cinema in its singular vision, i.e. a haunted house movie extrapolated within a town, and in Carpenter's adept manipulation of the audience instead of focusing on the more derivative, psychosexual aspects, the use of psychological horror and scares build towards an onslaught of murders relatively restrained by today's standards. At its core, combined with appropriate musical cues from the keyboard score, the exuding dread and classic components of the genre, "Halloween" is a powerful, menacing indie movie that has become a staple of horror cinema, a cogently written, stylishly shot and visceral experience in slow-building terror. Existing purely through inspiration and purpose, it is entirely deserving of its acclaim and worthy of repeat viewings.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Ghost in the Shell review

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 7 October 2019 05:14

(A review of Ghost in the Shell)

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 7 October 2019 05:14

(A review of Ghost in the Shell)Languid pacing and sinuous premise notwithstanding, "Ghost in the Shell" succeeds brilliantly as both an anime and a standalone, exhilarating mix of sleek yet gritty, hard-edged visuals, cyberpunk imagery and propulsive, action-packed thrills. Wholly undiluted and cerebral in its gambit, scope and execution, the film's cross-genre dexterity, majestic character designs, methodically detailed settings, colouring and CG serve to implement and sustain mesmeric inscrutability in spite of its relatively concise run time and unusually literary dialogue. It may even be too mind-expanding, philosophically expository and opaque for nascent fans of the medium, but the film will indeed strike a chord with those directly affected by its subject matter, i.e. body dysphoria, displacement and identity crisis. With its dream-like quality, dazzling futuristic cityscapes and themes of transhumanism, metaphysics and socioeconomic international marketplace, "Ghost in the Shell" offers the uninitiated a complex work of speculative fiction of such universality, depth and substance, it needs to be reflected on, digested and reappraised in order for its immersive, singular world, as well as its wealth of themes, intricacies and nuances, to be fully comprehended and inseminated. Superb, highly atmospheric and emotionally augmented by a soaring soundtrack and character study, the film rarely falters; it remains a remarkable entry into the Japanese animation canon so pregnant with roboticized culture and metaphysical theory that it demands to be viewed more than once.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Miseducation of Cameron Post review

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 6 October 2019 05:46

(A review of The Miseducation of Cameron Post )

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 6 October 2019 05:46

(A review of The Miseducation of Cameron Post )Postulates a rather pointed theory that conversion therapy not only does not work, but those in charge of the proceedings are merely as troubled, conflicted and ignorant as the people they are attempting to recondition. I was not bored, and it is oddly poignant and authentic in its character dialogue and interplay, however, it is perhaps too faithful to its source novel, which, all in all, was rather weak in its attack of the very subject it was supposed to dissect, but maybe my interpretation of it was wholly incorrect?

In my cynical opinion, the far less pretentious and serious "But I'm A Cheerleader", in all of its schematic, offbeat indie weirdness and comical hi jinks, is far more biting, entertaining and ultimately, worthy of repeat viewings, whereas this film deserves to be seen, but only the once.

In my cynical opinion, the far less pretentious and serious "But I'm A Cheerleader", in all of its schematic, offbeat indie weirdness and comical hi jinks, is far more biting, entertaining and ultimately, worthy of repeat viewings, whereas this film deserves to be seen, but only the once.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Christine review

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 5 October 2019 07:23

(A review of Christine)

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 5 October 2019 07:23

(A review of Christine)Few films mine the past in such a veiled, foreboding sense as John Carpenter's "Christine", but even if his efforts do not quite coalesce in terms of pacing and plot, the film's characterisations, zippy dialogue, slick visuals, nostalgic soundtrack (utilised to great effect during murder sequences) and vehicular stunts all thankfully aggrandise the proceedings, thus saving it from becoming a generic adaptation of a lesser Stephen King novel. It may not be as effective in totality as it is in fragments, but even Carpenter's weakest fare retains entertainment value, and this is no exception; not succeeding as a singular work exalts it as a classic in the 1980s horror canon by virtue of its daringly implausible premise. Owing to Carpenter's deft ability to imbue seemingly incredible stories with sheer escapism, panache and fun, it is entirely conceivable that a browbeaten, bullied 17-year-old nerd is freed and transformed by his inexplicable predilection towards and obsessional love of a malevolent Plymouth Fury with a maniacal mind of its own that drives autonomously (usually with intent to kill) miraculously self-repairs and plays endless rock'n'roll tunes at will. Despite its inherent flaws, the film is one of a kind thanks to its poignant finale, technical merits and ludicrous story basis, and therefore deserves to be deemed essential for fans of the genre, even if it isn't top tier Carpenter or King.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

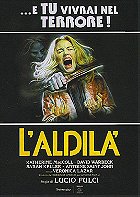

The Beyond review

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 2 October 2019 07:26

(A review of The Beyond)

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 2 October 2019 07:26

(A review of The Beyond)Equivocal and weak in the pre-production department even by European horror standards, "The Beyond" is nevertheless a deft exercise in schlock, off-kilter atmospherics and overall execution rather than authenticity and plausibility, and therein lies the method to viewing it. Fulci crafts a loose framework of a gateway to hell existing beneath a woman's new property within which he assays a series of hallucinogenic set pieces that one should not apply logic to, or expectations of it would certainly fall short. Showcasing rudimentary splatter effects both strangely hypnotic and proficient enough to induce revulsion, the film's graphic moments are a true marvel to behold, although tarantulas tearing out tongues may elevate the experience into excessive gore territory for viewers of a certain disposition. Such extended, protracted shots of forcibly erupted eyeballs or scorched, decayed corpses only enhances the bizarre vagary of it if all; watch it for what it is, which is an unapologetic, overt illustration of style without substance. Despite being wholly psychedelic, freaky and resplendent in its fractured visual and narrative structure in which only the decomposed cadavers in the immediate vicinity are awoken, "The Beyond" is not a zombie film, it is akin to experiencing a drug-induced nightmare and should be viewed as such in order to even watch it in its entirety without stopping to pick apart its non-existent plot. Refrain from questioning any of its overriding faults, of which there are many if you are the critical, pedantic type, and you will be rewarded with a vivid foray into Fulci's twisted, incomprehensible world.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

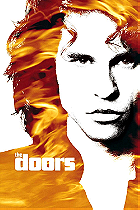

The Doors review

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 14 September 2019 02:06

(A review of The Doors)

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 14 September 2019 02:06

(A review of The Doors)On his first lesser outing as director, Oliver Stone's disjointed biographical music film centres on the rise and fall of The Doors, one of the more successful genre-bursting rock bands of the 1960s, but in actuality targets their larger-than-life frontman, Jim Morrison, and therein lies the first of many missteps in the attempt to maximise on such a wealth of material. An opportunity wasted, in my opinion, whereby subtlety falls victim to the pursuit of pretentious self-indulgence and bombastic flair tailored for the MTV generation. Stylistically staid and historically inaccurate, Jim Morrison's early life is barely explored, with Val Kilmer's showy, disconnected performance failing to capture any component of his true personality. Instead of the sensitive poet he probably was, Jim Morrison is portrayed as a sociopathic hypocrite who appears to initially embrace the 1960s counterculture lifestyle before becoming an amoral, uncouth and puerile drunkard. Scarce essence of either the band or its driving force is felt, with Stone foregoing the intricacies of their personal interplay and unified creative output to dwell on convoluted hallucinatory motifs and the unfavourable personality traits of the band's iconoclast. Biographical dramas should endear rather than alienate their intended audience, and "The Doors" is a turgid recreation of actual events, with its fallacy-laden depiction of a rock star poet and overblown, cliched composites of real accounts and persons within a fictionalised cartoon atmosphere. Frankly, the film's script is too restricted to fully communicate or deliver its point, thus failing to achieve its lofty ambitions or even capitalise on its basic conceit, but it is worth a look if you can ignore its vast shortcomings, i.e. a weak, uninspired narrative and flawed characterisation.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

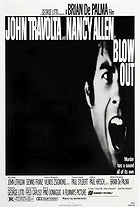

Blow Out review

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 14 September 2019 07:59

(A review of Blow Out)

Posted : 5 years, 9 months ago on 14 September 2019 07:59

(A review of Blow Out)De Palma pours the sum total of his talents into what is now viewed by many to be his magnum opus, "Blow Out". John Travolta (in a career-best turn) impeccably portrays a movie soundman and surveillance expert who inadvertently records the assassination of a Presidential hopeful. Operating as an instigating progressive for the narrative, the electrifying murder itself, dissected and rewound within the film, boldly unveils the complex, mysterious, illusory and seductive power of filmmaking as the obsessive, fanatical process that it truly is.

By way of exploring a vast litany of themes including paranoia, voyeurism and technology, De Palma realises his most downbeat, loaded homage to Hitchcock, and yet, whilst derivative of American cinema of the 1950s and 1970s, "Blow Out" also references British cinema of the 1960s, particularly its namesake, Antonioni's art film "Blow-Up". Exposing the machinations of filmmaking and politics with reverberating narrative depth, "Blow Out" employs intricate, nuanced layering through a cynical, conspiratorial and carnal prism, meaning that De Palma's tendency to veer towards style over substance with his work does not apply here; his cinematic pathology, psychology and choreography converge flawlessly, achieving thematic resonance by navigating his fantasy world (divided personalities, porno set pieces, technical gimmickry, split-screens opening up a self-contained world and new perspectives of situations, movies-within-movies, socially relevant characters at cross purposes, variable identities, sensibilities and worldviews that match his own) whilst acknowledging stark, blunt-edged reality through gymnastic camera work, black-comic dialogue and emotion-laden imagery.

Coded, stunning photography, dense plot and suspenseful set pieces are all harnessed by De Palma to expound his trademark audacious perfectionism, sinister elegance and stylistic flair, but "Blow Out" crystallises its pop culture allusions in baroque, fluid form, sustaining alacritous momentum before adopting an unhinged pace at its heart-stopping climax and profoundly tragic end executed with precision detail. Scathing in its dissection of the very landscape it celebrates, the tonally sardonic examination of corruption and dissent within government pervades through every aspect of the film, which is generally unrelenting in its multi-faceted, voluptuousness, however, with more political overtones than sexual, De Palma is able to earnestly explore crime and horror through a new darkly poetic lens. "Blow Out" is a personal culmination of recurring ideas, themes and styles imbued with poignancy and ripened artistry that evokes all of De Palma's dynamic yet flawed previous work and expertly supersedes it, crafting a capacious, virtuoso aesthetic experience that will render you at once unequivocally destabilised, mesmerised and emotionally destroyed.

By way of exploring a vast litany of themes including paranoia, voyeurism and technology, De Palma realises his most downbeat, loaded homage to Hitchcock, and yet, whilst derivative of American cinema of the 1950s and 1970s, "Blow Out" also references British cinema of the 1960s, particularly its namesake, Antonioni's art film "Blow-Up". Exposing the machinations of filmmaking and politics with reverberating narrative depth, "Blow Out" employs intricate, nuanced layering through a cynical, conspiratorial and carnal prism, meaning that De Palma's tendency to veer towards style over substance with his work does not apply here; his cinematic pathology, psychology and choreography converge flawlessly, achieving thematic resonance by navigating his fantasy world (divided personalities, porno set pieces, technical gimmickry, split-screens opening up a self-contained world and new perspectives of situations, movies-within-movies, socially relevant characters at cross purposes, variable identities, sensibilities and worldviews that match his own) whilst acknowledging stark, blunt-edged reality through gymnastic camera work, black-comic dialogue and emotion-laden imagery.

Coded, stunning photography, dense plot and suspenseful set pieces are all harnessed by De Palma to expound his trademark audacious perfectionism, sinister elegance and stylistic flair, but "Blow Out" crystallises its pop culture allusions in baroque, fluid form, sustaining alacritous momentum before adopting an unhinged pace at its heart-stopping climax and profoundly tragic end executed with precision detail. Scathing in its dissection of the very landscape it celebrates, the tonally sardonic examination of corruption and dissent within government pervades through every aspect of the film, which is generally unrelenting in its multi-faceted, voluptuousness, however, with more political overtones than sexual, De Palma is able to earnestly explore crime and horror through a new darkly poetic lens. "Blow Out" is a personal culmination of recurring ideas, themes and styles imbued with poignancy and ripened artistry that evokes all of De Palma's dynamic yet flawed previous work and expertly supersedes it, crafting a capacious, virtuoso aesthetic experience that will render you at once unequivocally destabilised, mesmerised and emotionally destroyed.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Login

Login

Home

Home 4 Lists

4 Lists 55 Reviews

55 Reviews Collections

Collections